106 people pressed ❤ and 18 people found it worth a retweet when Ivo Gabrowitsch wrote: “If I had one wish, I’d wish for less ‘inspired by’ and more ‘solves this problem’ typefaces.” It is hard to disagree with what he says – but it is also hard to disagree with Ksenya Samarskaya’s reply: “Best ones do both, no?” This post is about what I consider to be a successful example of doing both.

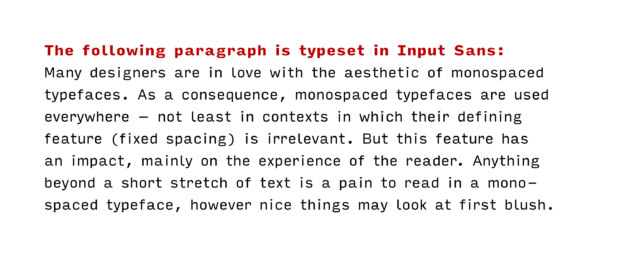

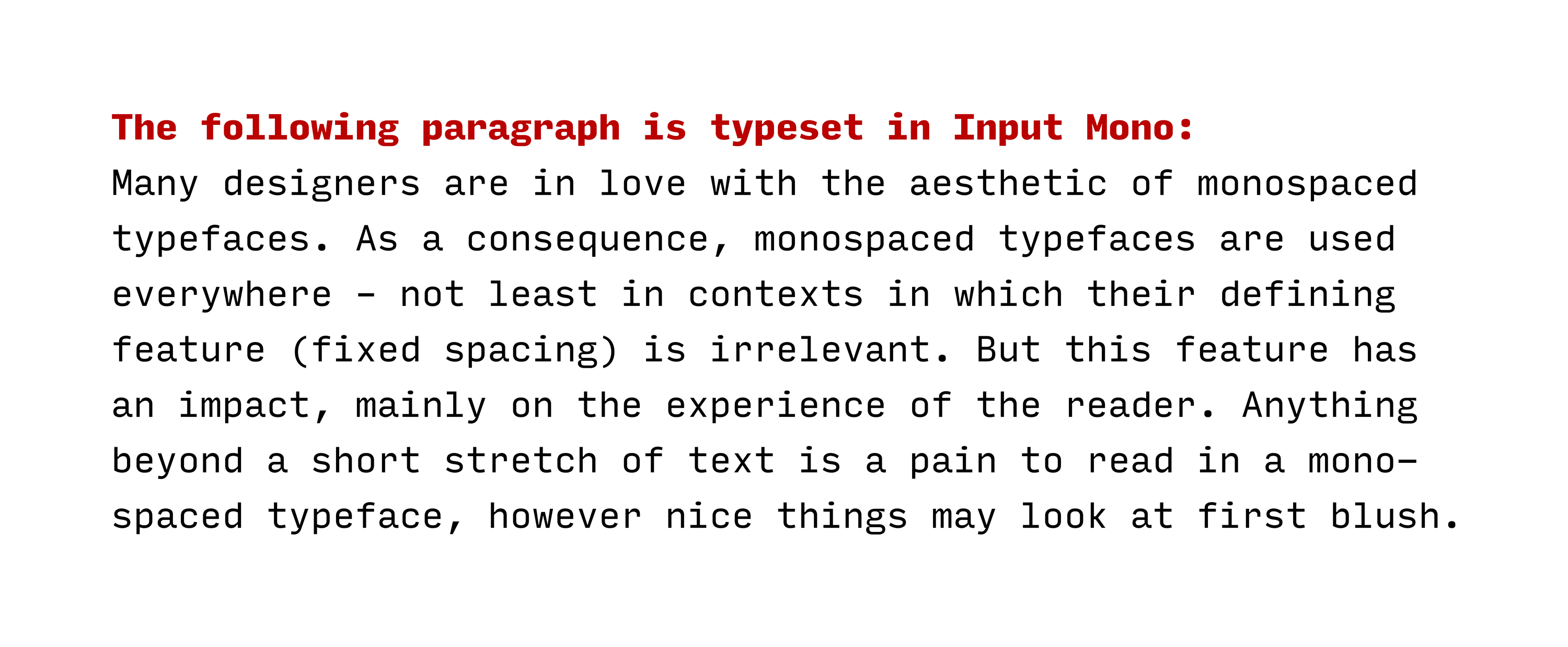

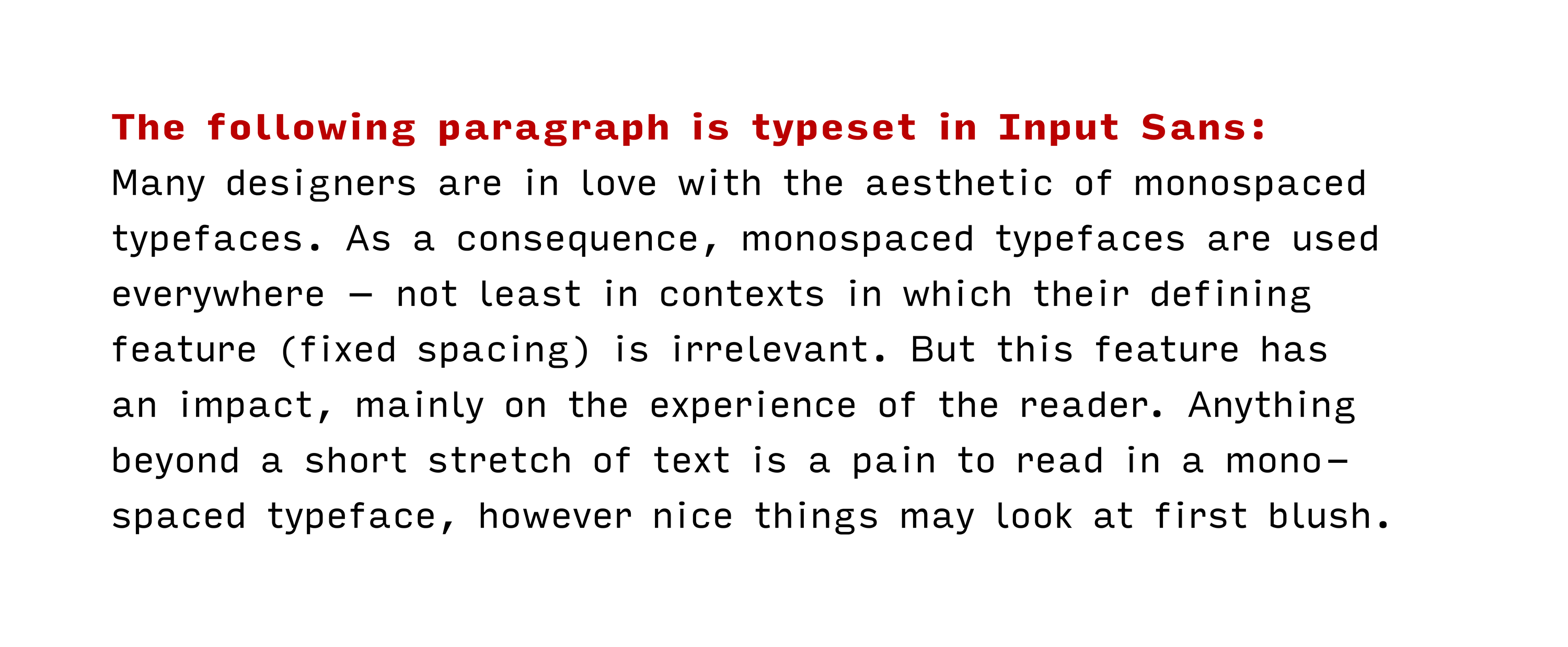

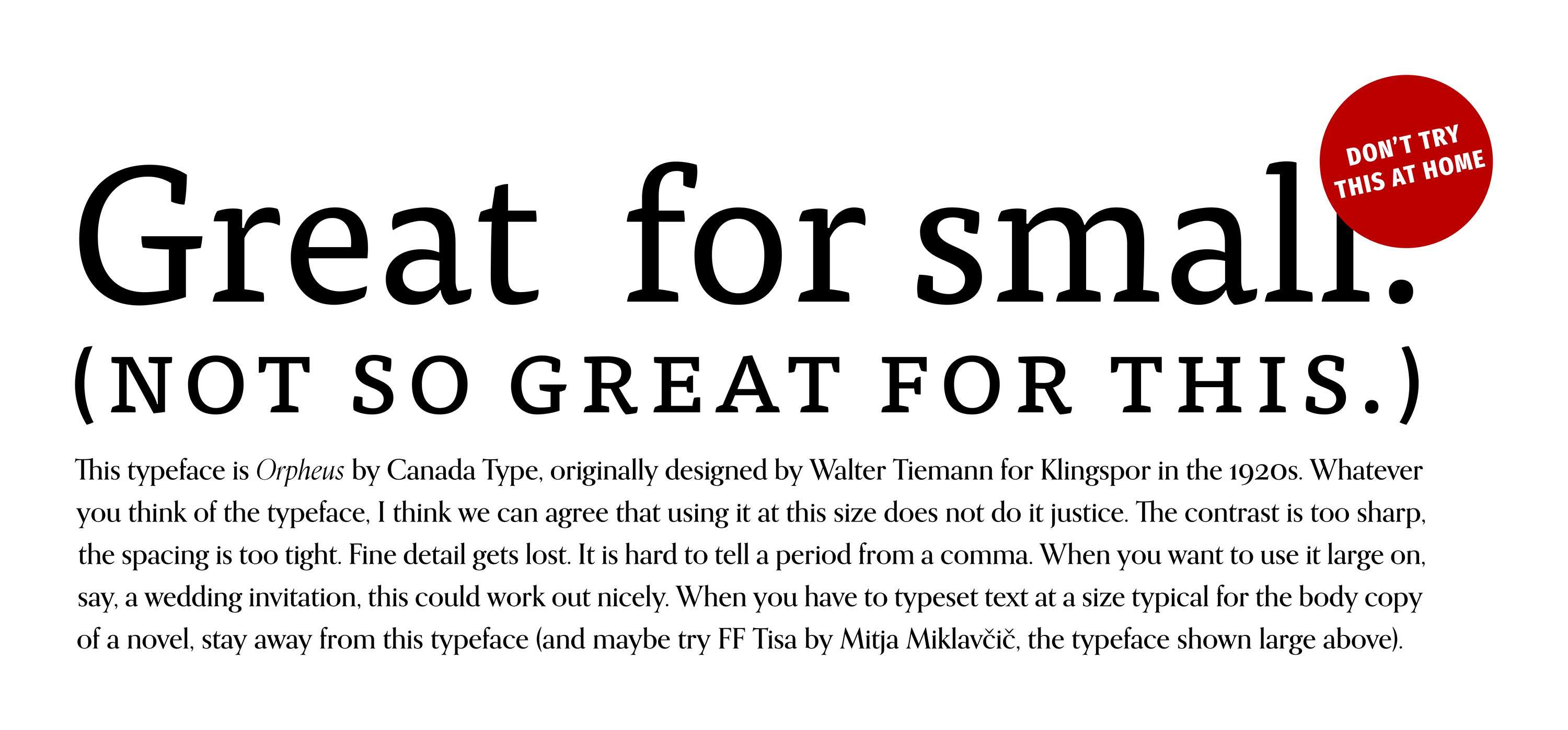

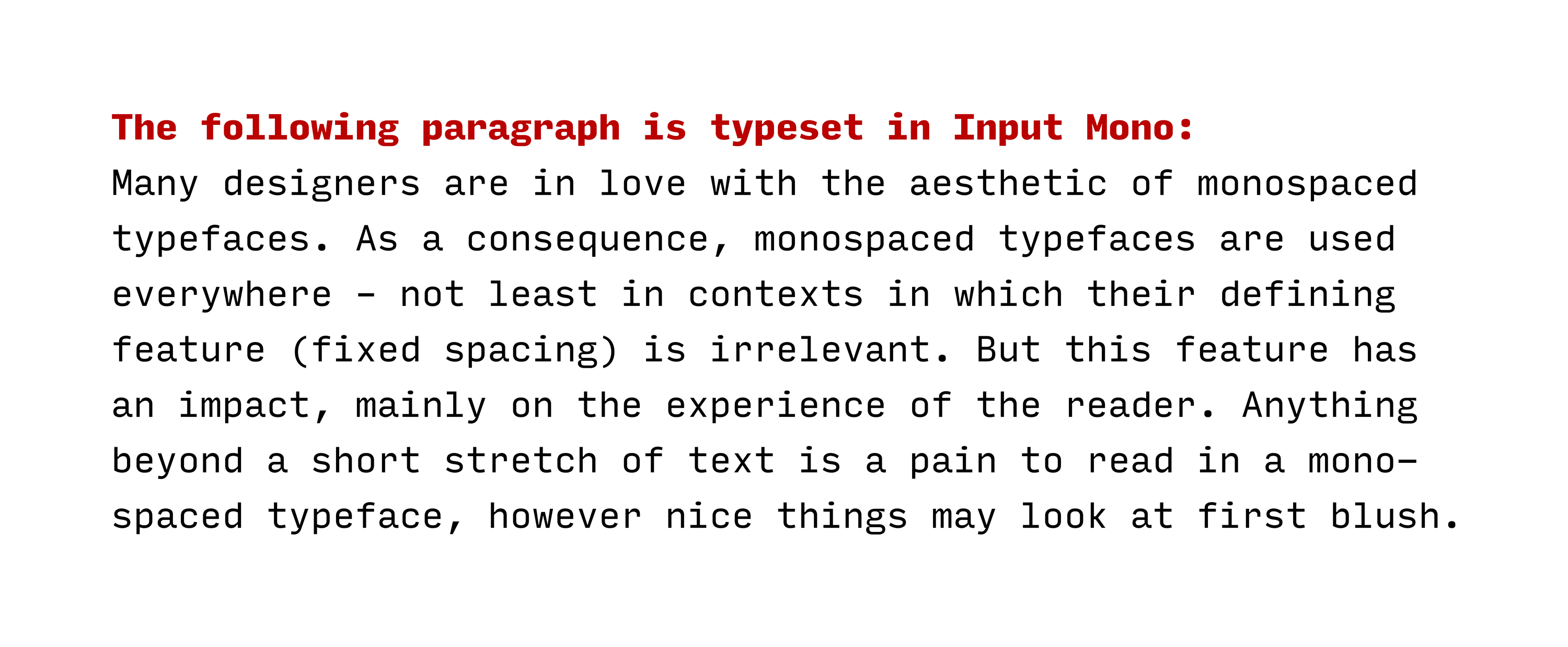

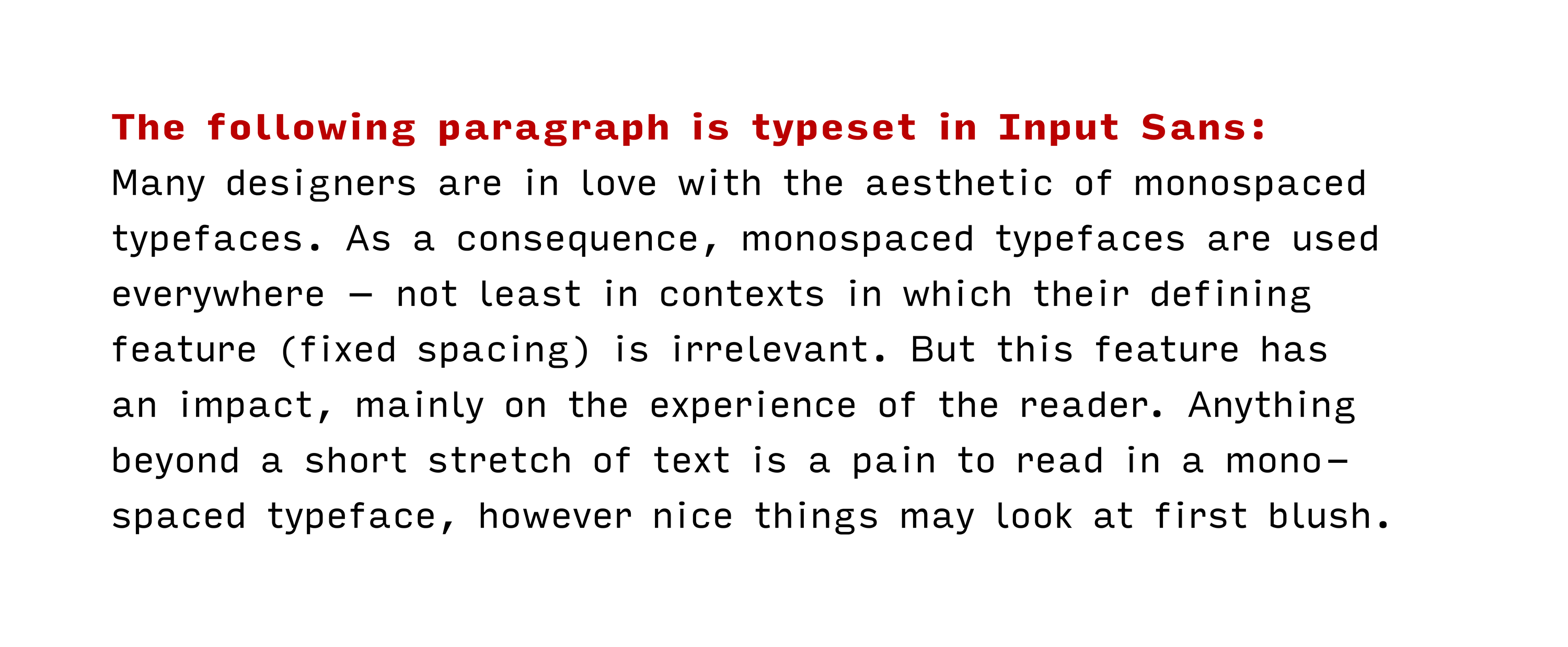

Many designers are in love with the aesthetic of monospaced typefaces (i.e., typefaces in which each character occupies the same amount of horizontal space, as opposed to proportionally spaced typefaces in which character widths are independent of one another). The appeal of these typefaces may stem from some kind of nostalgic association with typewriters or from their use in technical environments (computer terminals, programming etc.). Maybe it’s both. In any case, the fascination is there. As a consequence, monospaced (or fixed-width) typefaces are used everywhere – not least in contexts in which their defining feature (fixed spacing) is irrelevant. But this feature keeps on having an impact, mainly on the experience of the reader. In monospaced typefaces, glyphs have to be wider or narrower than in typefaces without the fixed-width constraint in order to fit everything in the space that is available while keeping the spacing optically balanced. The result is not what most designers would like to set a novel in and it’s not what most readers would like to read a novel in. Actually, anything beyond a short stretch of text is a pain to read in a monospaced typeface, however nice things may look at first blush.

Type designers have found a solution to this problem. It’s not a new solution, but it is a solution that I think deserves more attention (hence this post). Type designers have created typefaces that look like monospaced typefaces, but actually use proportional spacing. The benefit: Designers get to keep the look they love, but readers don’t have to go through the pain of a true mono. Such typefaces – some call them ‘monofaked’ or ‘fauxnospaced’ – are easier on the eyes than the ‘real thing’. It is a balancing act for type designers to keep enough elements of typical typewriter fonts in order to avoid losing the appearance, while at the same time making substantial improvements to reading ease.

The first typeface that fits this description was apparently one called Bulletin Typewriter: Released in metal as a monospaced font, it became available with proportional spacing in phototype and transfer lettering formats. The earliest in-use example of the proportionally spaced Bulletin Typewriter I am aware of is from 1973. American Typewriter was released not much later. In the following list of other typefaces in this category, I will – as usual – apply a liberal interpretation of any relevant criteria: Any typeface that vaguely looks like a console or typewriter typeface (read more about this term in an article by María Ramos) has a ‘monospaced appearance’ in my book. For a change, the sorting will be chronological rather than alphabetical to emphasise developments in this genre.

Proportionally spaced typefaces with a monospaced appearance

- 1973: Bulletin Typewriter by Morris Fuller Benton (Mecanorma)

(The link refers to a digital version of the metal monospaced typeface, originally released in 1933 by ATF. A proportionally spaced version was only available in phototype and transfer lettering formats. It’s in the list mainly for reference.)

- 1974: American Typewriter by Joel Kaden & Tony Stan (ITC)

- 1989: Officina Sans & Serif by Erik Spiekermann & Just van Rossum (ITC)

- 1996–98: Letter Gothic Text by Albert Pinggera (FontFont)

- 1999: TypeStar by Steffen Sauerteig (FontFont)

- 2000: Bs Monofaked by Mário Feliciano (Feliciano Type Foundry)

- 2000: New Letter Gothic by Gayaneh Bagdasaryan (Paratype)

- 2001: Courier Sans by James Goggin (Lineto)

- 2007: Newsletter by Ingo Krepinsky (Die Typonauten)

- 2008: Generika by Alexander Colby (Milieu Grotesque)

- 2008: Lacrima Senza & Serif by Alexander Colby (Milieu Grotesque)

- 2008–2010: Lekton by Luciano Perondi and students at ISIA Urbino (Google Fonts)

- 2010: Typewriter by Henrik Kubel (A2-TYPE)

- 2011: Hellschreiber Sans & Serif by Jörg Schmitt

- 2011: Relative Faux by Stephen Gill & The Entente (Colophon Foundry)

- 2011: Signika by Anna Giedryś (Google Fonts)

- 2012: Anaheim by Vernon Adams (Google Fonts)

- 2012: Executive by Gavillet & Rust (Optimo)

- 2013: Documan by Martin Vácha (Displaay Type Foundry)

- 2014: Input Sans & Serif by David Jonathan Ross (DJR)

- 2014: Queue by Tal Leming (Typesupply)

- 2014: Triplicate by Matthew Butterick

- 2015: Clone by Lasko Dzurovski (Rosetta)

- 2016: Millimetre by Jérémy Landes (Velvetyne Type Foundry)

- 2016: Operator by Andy Clymer (Hoefler & Co.)

- 2016: Proportional by George Triantafyllakos (Atypical)

- 2017: Attribute Text by Viktor Nübel (FontFont)

- 2017: Bitcount Prop by Petr van Blokland (TYPETR)

- 2017: Comspot Tec by Nils Thomsen (TypeMates)

- 2017: iA Writer Duospace (based on IBM Plex Mono by Mike Abbink & Bold Monday)

- 2017: Ultraproxi by Ray Larabie (Typodermic Fonts)

- 2018: Clincher Duo by Alexander Lubovenko (ParaType)

- 2018: Covik Sans Mono by James Edmondson (OH no Type Co)

- 2018: Drive Prop by Elliott Amblard & Jérémie Hornus (Black[Foundry])

- 2018: Tuner by Simon Renaud (Production Type)

- 2019: Recursive Sans by Stephen Nixon (Arrow Type)

This list started on Twitter. Thanks to Reed Reibstein, David Jonathan Ross, George Triantafyllakos, Daniel H., Dave Coleman, Anthony Masure, Martin Wenzel, Frank Adebiaye, Michael Piotrowski, Akira Yoshino, Eric Mellenbruch, Max Phillips as well as the people from Studio Het Mes, Fonts In Use and Displaay Type Foundry for suggesting typefaces. If you know of any additional typefaces that may qualify, please get in touch.