Het Gronings is, net als veel andere dialecten, niet op alle deelgebieden van de linguïstiek even goed bestudeerd. Aan de semantiek – of meer specifiek: de woordenschat – wordt buitenproportioneel veel aandacht geschonken want woordkeus springt in het oog van zowel de leek als de vakman. En er is blijkbaar veel over te zeggen, ook al maakt het, volgens Ede Staal, niet uit of de bakker ‘brood’ of ‘stoet’ bakt. De met name verbale morfologie van het Gronings staat centraal in twee werken van Siemon Reker: zijn proefschrift (1989) en de onvoltooide Groninger Grammatica (1991–1996). Veel minder studies zijn verricht op het gebied van de pragmatiek, de syntaxis alsmede de fonologie en fonetiek. Mijn belangstelling in dit stukje geldt de laatste, de fonetiek. Omdat dit geen bachelorscriptie is, maar slechts een in de kleine uurtjes ontstane blogpost, beloof ik niet meer dan een eerste verkenning van het terrein. De lacunes in de wetenschappelijke kennis kan ik daarmee nauwelijks opvullen, maar misschien vragen opwerpen die later door anderen kunnen worden beantwoord.

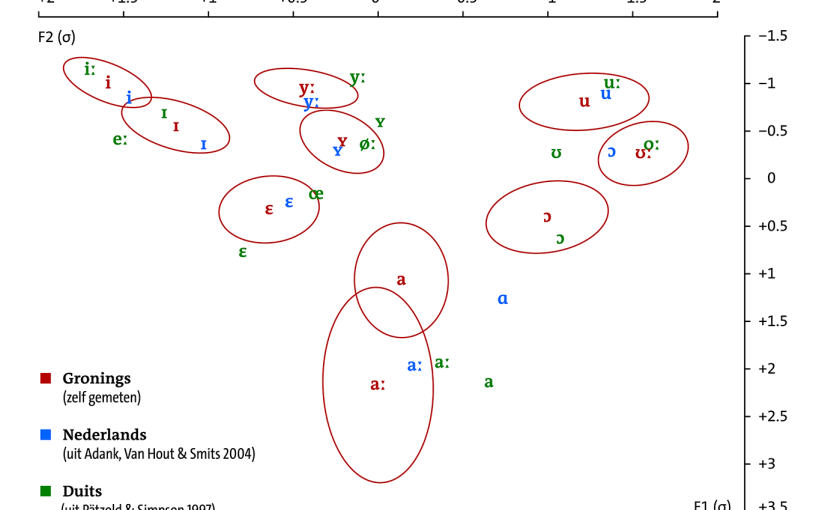

Het onderwerp van mijn onderzoekje is de klinkerproductie van één spreekster van het Gronings. Hiervoor heb ik gebruik gemaakt van de opnames op de website van de Liudgerstichten die een aantal passages uit de Groningse vertaling van de Bijbel heeft laten inspreken door vrijwilligers. In totaal komen er een stuk of vijf sprekers langs, maar er was slechts één van wie opnames van toereikende lengte beschikbaar waren. Ik weet het niet zeker (en heb ook niet de moeite gedaan om na te vragen), maar ik denk dat de teksten die ik heb gebruikt, zijn ingesproken door Riemke Bakker, de secretaris van de Stichting Grunneger Toal. Als zij het is, gaat het om een spreekster die in Bedum – in het zuidelijke deel van het Hogeland – woont, maar van wie ik niet weet waar zij is opgegroeid. Het doet er ook niet toe want ik heb toch geen vergelijkingsmateriaal van sprekers uit andere regio’s. Van elke beklemtoonde monoftong (eenklank) die zij in de opnames produceert, heb ik 20 exemplaren geanalyseerd (voor zover er 20 te vinden waren, zie beneden). Ik heb de voorkeur gegeven aan klinkerexemplaren die door een plosief (plofklank) worden voorafgegaan en gevolgd. De grens tussen medeklinker en klinker is in deze gevallen scherper dan bij fricatieven (wrijfklanken) of liquida (vloeiklanken) waardoor de klinker ietwat minder in zijn kwaliteit wordt beïnvloed. Niet bij alle klinkers was het mogelijk om deze strikte selectiecriteria aan te houden, maar ik heb er in ieder geval op gelet om zo min mogelijk klinkers te analyseren die door een /r/ of /l/ worden gevolgd. Wie de uitspraak van de ‘oo’ in ‘rood’ met die in ‘door’ vergelijkt, hoort hoe sterk de invloed van een /r/ aan het einde van de lettergreep op de klinker kan zijn.